Jess Jones —

The second I started this project, I knew Jess would have something interesting to say about process. She’s a textiles professor at Georgia State University’s Ernest G. Welch School of Art & Design, has been an artist in residence at the Appalachian Center for Craft, and at one point took me to see the quilting work of Ben Venom. We caught up recently and talked about new work, process, and the ways she approaches art.

Jess

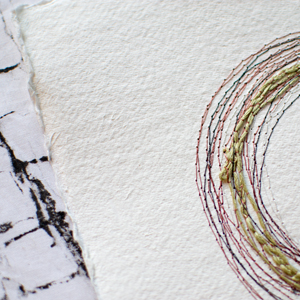

I’ve been interested in forms that are not necessarily what we know to be art forms. The use of fabric. The use of traditional quilting. The use of some mixed media—thread, basketry, weaving—I’m interested in those things that aren’t completely craft or art. They’re sort of in between those two worlds. I like things that don’t fit. I think my process has a lot to do with things that don’t fit into categories and working with tension between two ideas, dualities, things that oppose and have to coexist.

And I’m interested in how certain categories are defined. So defining drawing by a work on paper. Or saying a print is a matrix from which there are multiples. That opens up opportunities to see things differently. A quilt is layered and stitched fabric, and something quilted is simply layered and stitched, so there are many possibilities in thinking about that. I also like thinking about functionality—when is something a useful object or a decorative one… I don’t make work that is useful, but I like forms that are utilitarian and are very heavy with associations. My work is often about things that are familiar and unfamiliar, so I play off of these kinds of forms.

Paul

Tell me about how place changes the way you approach the creative process.

Jess

What I was reflecting on—living in a more remote place—I was taking a lot of photographs of fabric—clothing in particular—and printing it out on fabric and exploring a more interior world because Appalachia is know for these pockets of isolated communities. It gave me this little place within which to be very contemplative. I like Atlanta now, but when I first got here, I described it as “aggressively non-contemplative.” So my work has a lot to do with how I navigate through this environment. As that environment changes, so does the work.

Weaving

What’s really fascinating about this is, in my artistic process, I don’t have the patience for hand-sewing. I actually machine sew a lot—and I often use the sewing machine as a drawing tool.

Jess

I’m interested in issues of labor surrounding textiles. We’re really concerned with where our clothes come from, but we’re not really that concerned. Textiles is one of those things we’re not really willing to pay for yet and do with less. We’re more willing to pay for artisanal food, even aspects of our houses that are custom and done by artisans. Although there’s a lot of recycled clothing going on, we don’t really value still labor of textiles, or understand how much it really takes.

Paul

You worked in a textile factory at one point too, right?

Jess

I did. And I don’t know any other textile artists who have sewn on the line in manufacturing. I did that for about a year and it didn’t teach me too much about textiles, but it made me much more aware of what that kind of work is actually like. It profoundly influenced how I think about textiles. When I encounter commercial textiles, I see the world that made them.

What’s really fascinating about this is, in my artistic process, I don’t have the patience for hand-sewing. I actually machine sew a lot—and I often use the sewing machine as a drawing tool. When you talk about construction of something and the value of handmade, I think the slow and the handmade is better sometimes. Does something need to be hand-stitched to be handmade? Can’t it be machine-made and still be handmade? It’s handmade by me, but I made it on a sewing machine! I like thinking about how and why people draw that boundary. That fascinates me.

Jess

So thinking along those lines, I’ve been interested in working with these quilts I find at thrift stores. For a while I was buying these hand-pieced quilt tops [the front side of a quilt] with hundreds of hours of labor invested in them. If we really value handmade things, why were these ever discarded? I am wondering what can I do with these objects intended to be heirlooms. I might not make anything with them that is interesting, but I know that I wouldn’t even have the time to have a career if I had to make work like this that is completely hand stitched. I also like thinking that I might end up having an anonymous collaborator if these pieces ever develop.

You can tell a lot about the makers of these quilts and I like thinking about who they might be...I love finding the mistakes in the quilts I’ve found, where the thing is flipped a little bit. The pattern will be messed up. I love finding those. You really see the hand and it just makes the piece real.

I am sure other people have said this but at times my work is like a really bad boyfriend. I wake up and and it tells me ‘Baby, things are going to be different today,’ and I get in there and really try to make things work.

Jess

Along the same line as using images of graffiti, I’ve started to work with different maps of Atlanta. And what I’m thinking about doing with these quilts is imposing maps on top of them. This piece might be the start of something. It’s a handmade, hand-pieced quilt and over the top of it is a map of income segregation. I’ve been using the overhead projector for this. This quilt is inspired by Melissa—a former student. Her artist statement said “I always wondered what it would take to change my stars.” The deck was completely stacked against her in so many ways and I think she really did change her stars and I’ve been inspired by that ever since. So I started thinking about how someone could change their stars. And stars is the motif in the quilt. I’m interested in making a dozen different maps on this one piece that have to do with your stars. Over the top of this map will be a map of all the psychics in Atlanta. A map of all the startups. A map of all the campuses. Things that could potentially change your life or predict your life or set you on a completely different path. Again, I don’t know if this layered mapmaking is going to work anywhere but in my head, but we’ll see.

Process is a hard term to define. There’s actually a weaving book called "This Is How I Go When I Go Like This." There are these things you can’t put into words, or certain step-by-step techniques. What we call tacit knowledge.

People talk about divergent and convergent thinking. People that are divergent think about process like ‘this thing leads into this other thing that leads into this other thing’ and so on. I do the opposite of that. I’m completely convergent. All of the things that I work on—whether it’s baskets or papermaking or weaving—all of it focuses inward and I like seeing similarity and pattern. Sometimes I wish I was more exploratory and I didn’t just live in this weird hall of mirrors with my own thoughts. But I think the tension between my thought process and my environment is what comes out in my work.

Jess Jones’ studio in Atlanta

Sometimes I’ll call people when I’m exploring an idea and I’ll send them a photo and ask ‘Is this anything?’ kind of like when David Letterman would do that sketch on his show where someone would perform a stunt and then the audience would decide by volume of applause if that was anything. You know?

I am sure other people have said this but at times my work is like a really bad boyfriend. I wake up and and it tells me ‘Baby, things are going to be different today,’ and I get in there and really try to make things work. And I feel like every day is kind of a disaster because I’m not totally in charge of that person—which is my work—but it’s a give-and-take where I have to ask questions. What is it you want to do? Why won’t you do these things for me? Can’t you just decide?! I feel like I constantly have these conversations with my work.