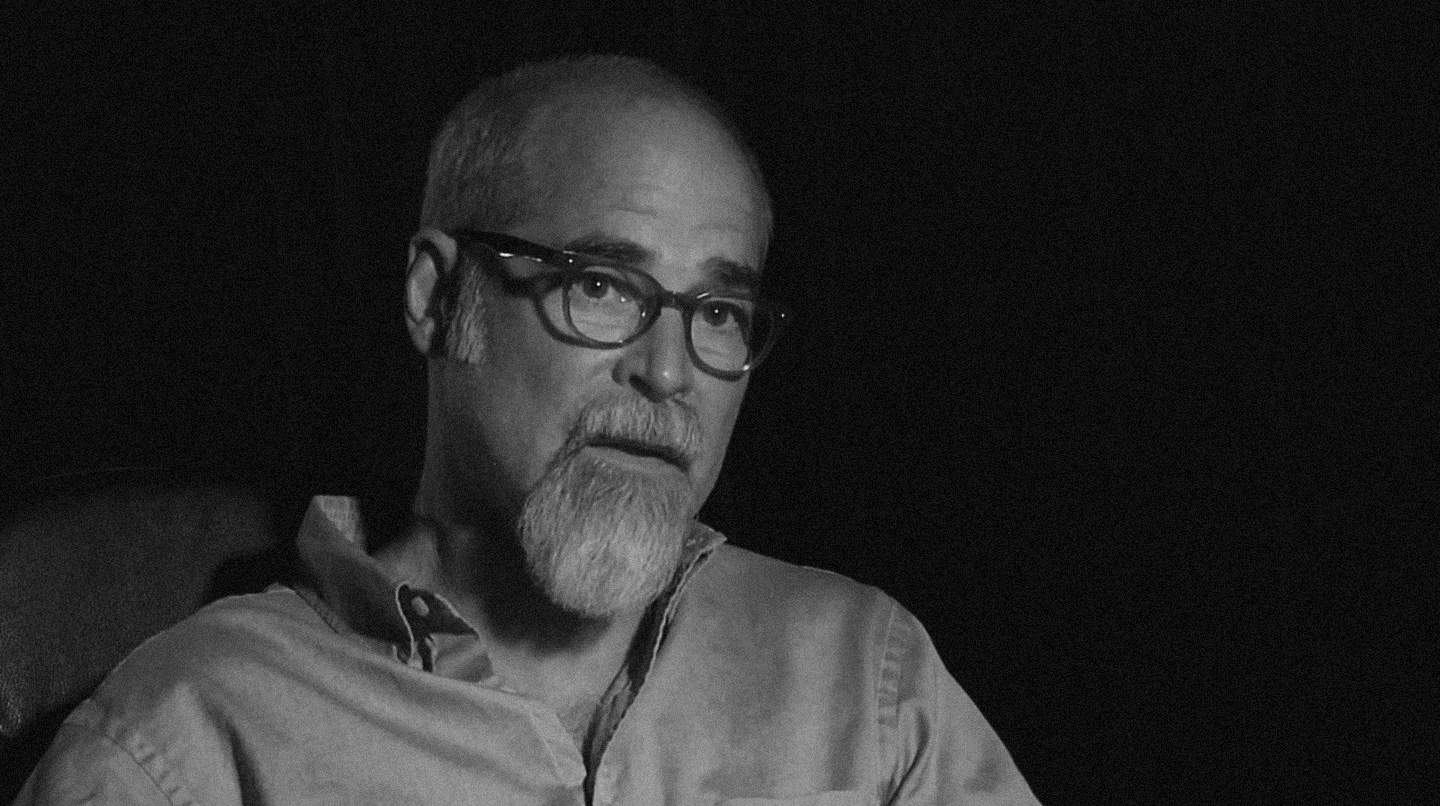

Don Howard —

Process is this thing that comes before the technique that leads to the product. It’s not how one necessarily gets ideas, but how the ideas find their way to us through our interaction with the world. Sometimes it’s the disappearance of those ideas that lead us to where we need to be.

I spoke with Don Howard—writer, editor, filmmaker, and professor—about process and his latest endeavor. The documentary, By the River of Babylon: An Elegy for South Louisiana, looks at the disappearing culture and wetlands in south Louisiana. Don has a background in philosophy and is the director of the only 3D production curriculum in the country at the University of Texas in Austin.

Paul

I’ve been really interested in talking to you about process, with your background in philosophy. Tell me a little about what that means to you.

Don

It’s extremely hard to talk about process. I’ve been trying to teach editing for about 15 years now, and I realized when I started reading textbooks that nobody really tries. They just talk about technique and ‘Here’s a shortcut to do this,’ or my favorite that always starts with ‘If you want to do this, I do it this way…’ and they show you an incredibly layered set of things to do. And you can follow it if you’re smart. But it always begs the question of whether you want to do that or not. Most beginners don’t know if they want to do that particular thing. I don’t know what I want to do until I’m halfway through it. So Can you help me with that part? I’m sure if you ask a question like that at a conference, people would start looking at you like you’re in the wrong place.

It’s a cool thing you’re trying to do and it’s really tough. It’s like saying ‘Where does a good idea come from?’ Even if you have them, you’re not in touch with how they came about.

It’s kind of strange to say that because our whole culture is about product now and consuming things and branding yourself. I deal with a lot of graduate students who are trying to figure out how to become good filmmaker s, and they seem to think it’s primarily about branding themselves. They rarely talk about process, and they don’t talk about technique all that much either. If they could just skip to the product part they’d be just fine, or at least they think they would be.

I guess I react wildly in the other direction. When I saw it written down as ‘Product’ it almost looked like ‘Dead body’ or ‘Finished’ or something. Being a working editor, you never have time to do everything you want, but you're always working, continuing.

And then the weirdest part for me—I don’t know if other people feel this way or not—‘Product’ is something I avoid even thinking about.

Don

When I have a movie like this—By the River of Babylon: An Elegy for South Louisiana—I could keep working on it as long as I have the nerve and the time. That’s why its taken so long and why it’s gotten better. I really don’t think about the product all that much. Once I’m aware that it’s a product, it’s almost shocking to me to realize that it’s done.

Don

Here’s the main thing to me: Americans have a tendency to romanticize artists, and we have a tendency to romanticize what they’re doing and probably inflate it. Many young filmmakers want to believe that they’re geniuses who are absolutely talented with film and everything they do is therefore great. And that there’s just every other schlub who doesn’t have the talent to do anything good. And I think that really messes people up. In a way it makes everything otherworldly. When you talk about process, that’s a real live thing. It’s a set of things you’re doing or it’s a verb, not a noun. Americans often want to see it as something easy. In other words, if you’re in the film world and you’re not Orson Welles, you don’t count. So a lot of what they do is romanticize what Orson Welles was or somebody like that. They have their geniuses they believe in and they idolize them and, in effect, separate them from reality. They don't want to talk about them as just regular people who struggled with their family lives and were running away into making films, maybe, and maybe that’s why they were actually so good: They put an inordinate amount of energy into it. We just don’t want to talk about it that way!

Instead, we always want to talk about the artists’ ‘Vision.’ I very much run the other way, because I don’t know what that means. When I look at the film By the River of Babylon, we were very much into that area (South Lousiana) and so we kept traveling out there. It’s a long way, so we’d have eight hours going and eight hours coming back, not to mention the time we were there to talk about why we’re doing this and should we be doing this? 'Who wants to see this anyway?' Looking at it now, I see that we did almost exactly what we intended to do. Between the time we were daydreaming about what we wanted to do and now, we never thought about it once. I never asked if we were 'being true to our vision.' We just did what we liked and did a bunch of really mundane shit! And we kept going!

I’m afraid a lot of people won’t take that music seriously as art. It’s really just dance music. I think we’re limited by that. The people who get that will love it. That’s the limit of our idea to begin with.

My impulse is always to downplay the metaphysical side of it. I had a tendency to think when we were shooting ‘Should we have him sing in French?’ or ‘Am I trying to force this too much?’ For someone who doesn’t really know anything about this, it’s a lot more mundane than it sounds. I have to really test that original idea. To go all in with it, I can’t waste time on a shitty idea!

The hardest part for me is coming up with the idea where I finally go ‘Yeah, let’s throw in on that. We’ll spend a few years thinking about that and working on that…’ In this film, the key for me was Beau Joque. We happened to see him in his heyday and it changed everything for me in terms of how I looked at that area. He was just the greatest.

That was a long time ago but it was what I hung on. When Jim Shelton and I decided to make this movie, he kept asking ‘What are we going to make this film about?’ I remember telling him it was about musicians who were so good and serious about it that you take regular music and turn pain into joy.

For those five or six years we never talked about our vision. He never asked me why we were making this movie. It’s a weird mix of hypothesis and testing. You turn the camera on and then you have to really listen.

When you romanticize your favorite filmmaker, it distances them from reality and it’s kind of demeaning to them. It’s a lot of hard work! Filmmaking is an extension of everything else that I do. It’s not a separate thing. It’s very much a regular part of my life.

Don

The deepest things I think about and care about, I want to figure out how to get them across in an hour or two.

If we got along and I was going to be near your area and we said ‘Hey, let’s take the evening and get a couple of beers and talk,’ you go through exactly the same process of ‘What do I talk about? What do I ignore? How do I present it?’ that you would with anything else. You don’t want to talk about the craziest thing you’ve ever done because it might make you sound insane. The other person may not have any way to connect to it, so you don’t ever go there. To me, filmmaking the same mental process. It’s the same process we have to make sense out of the world and communicate.

Kevin Courville and Phil Allemond

Paul

I'd love to hear your thoughts on the creative process as it lives outside any specific medium. Can you give me a bird's eye view?

Don

Even though it’s out of fashion now, I did read a lot of John Dewey and a lot of Pragmatism way back when I was studying philosophy. A lot of the way I look at film comes from the way the human organism deals with the world, just learning how to walk or think or communicate. It’s this constant interplay between hypothesizing something and then testing it to see what happens.

Physiologically and neurologically, that’s the way we learn and that’s the way we learn how to get along in the world. Humans have perfected it so much that it goes relatively deeply into emotional and intellectual constructs and concepts. I think documentary plays into that perfectly. All we knew when we were making this film was that there was something important going on when we heard Beau Jocque. The only reason he started playing accordion was because he was paralyzed for a while and he had nothing else to do. He had grown up around music and his dad was an accordion player. It was almost in his genes. As soon as he picked up an accordion he was good. And that music affected me so much, I began to wonder ‘Can we get it across to people who don’t know about this music how affecting it can actually be?’

The way this film developed, we decided to make a film about dance halls and we didn’t have any money. So we went with one roll of film, which is twenty minutes long, and all we did was drive around Louisiana for three days and shoot these old dance halls—most of which were falling down. We shot about sixty of them altogether. People glaze over immediately when you start telling them it’s a film about dance halls in Louisiana! We started realizing the wetlands was key to what we wanted to say as well. The final thing that triggered it all was that we realized ‘Every time we go out there, another dance hall is closed.’ These are big halls and we had only been shooting for three or four years and yet we were seeing them die right in front of us. So the film should be about culture dying and landscape dying.

To me, there’s a philosophic background that’s equally important to me, where even as a young person reading about philosophy, this whole process of learning and maturing in the world is a much more natural and everyday thing. It’s just how we’re built as humans. It’s the way we deal with the world, not a matter of flashing insight. You have to prepare for that realization. You have to keep going out to Louisiana all the time and at some point it’ll come to you because you’re picking things up.

If that works, then life can become a process of revealing itself to you. Not a matter of your own will forcing meaning on to things. This process might take years. But it’s a matter of just listening hard enough, and it gives us something to do with our lives! And meanwhile you’re also connecting with a lot of people you might not have been able to connect with.

“For now South Louisiana’s language, music, and culture continue to thrive here and there, like pockets of healthy marsh.”

Don Howard was born in Waco, Texas, and graduated with a B.A. in Philosophy from Baylor University in 1979. He first came to Austin to study philosophy at the University of Texas, but upon realizing that there are no Academy Awards given in the “Best Philosophy” category, he began directing and editing television and film; he graduated with a Master of Arts degree in Production from UT in 1988.

Mr. Howard has edited a wide variety of material for other directors, specializing in particular in documentary work, and he began teaching editing at the university in 1998. He has also directed and edited two of his own documentaries for PBS, Letter from Waco (1997) and Nuclear Family (2003), and is currently producing, directing, and editing By the River of Babylon: An Elegy for South Louisiana, which has been funded by PBS’s Independent Television Service and by the Guggenheim Foundation. Mr. Howard is also Production Area Head and the Director of the department's new 3D Production Program, UT3D.